The River Within the Watershed

Issue # 16

Geographers define watersheds as basins surrounded by mountains and ridges drained by streams that create a single river. A watershed is a living being, an ecosystem containing all of life, fierce, gentle, and overlapping. A watershed is one large drainage system: streams, springs, wetlands, and groundwater.

To imagine a watershed, cup your hands, palms up, and tilt them down slightly. Imagine the seam where the outside edges of your hands meet as a river and the lifelines on your palms as tributaries. Imagine pouring water into your hands; the water would run out over the tips of your little fingers like a tiny waterfall. You have just created a watershed.

In the wild, you can find the visible source of a watershed by locating the highest spring. I found the spring for my beloved Swannanoa River behind a row of U-Haul trucks near North Carolina Highway 70. In that place, three streams joined together. The Great Blue Heron was resting there until I disturbed her.

After the Civil War, Appalachia attracted northern industrialists. For most, access to resources was a persuasive draw, along with casual regulations about waste disposal.

Consider the German-born paper maker Harry Straus. With an eye to the probability of another war in Europe, Straus moved to New York and formed Champagne Paper Corporation with funding from American Tobacco and Phillip Morris. In early 1937, Harry Straus sought a southern location for his paper mill, preferably in North Carolina. His requirements were:

No less than 10,000,000 gallons of pure water a day.

Proximity of a railyard.

Availability of labor.

A locality not in the vicinity of a manufacturing center,

And, here I quote, “We do not want any interference on the part of the State in the disposing of our wastewater”.1

Straus purchased 225 acres on the Davidson River, close to where she flows into the French Broad River. Straus named his company Ecusta, thought to be Cherokee for Davidson River. The Transylvania Times announced: “Pure Mountain Water Was Deciding Location Factor.” Ecusta began production on September 2, 1939.

Paper production is a dirty business. Paper mills smell oddly sharp and slightly sweet from pulpy wood and industrial chemicals. On a flight back to visit her childhood home in North Carolina, a friend tried to determine what town they were flying over in their small plane. Catching the scent of a paper mill, she correctly declared they were over Canton, a North Carolina town known for paper production. Another friend’s father worked for a paper mill. He ran his car through the company car wash every day before heading home to shower off the rest of the stink.

Straus’ water requirements, both the extraction and his cavalier disregard for wastewater disposal, haunt me. For good reason.

By 2001, Ecusta was known as a distressed property that had outlived its productivity. Cleanup began in 2008 under the direction of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ). Three thousand two hundred tons of mercury and lead-contaminated soils were excavated and removed from Ecusta’s site. An additional 5,600 tons were removed from underneath the buildings. In 2009, the site was declared within acceptable EPA ranges. However, the area remains constantly monitored. The current owner plans to build a mixed-use development with 1000 housing units and 1,250,000,000 square feet of commercial space.

According to John E. Ross, author of Through the Mountains: The French Broad River and Time, Ecusta’s saga was repeated by most manufacturing industries that relied on water from the French Broad River and its tributaries. Paper mills like Eucusta and textile mills polluted the waters; then, they fell victim to the opportunists who bought and sold companies and eventually shut them down. Beacon Manufacturing, in Swannanoa, in the Watershed of the Swannanoa River Valley, was among them.2

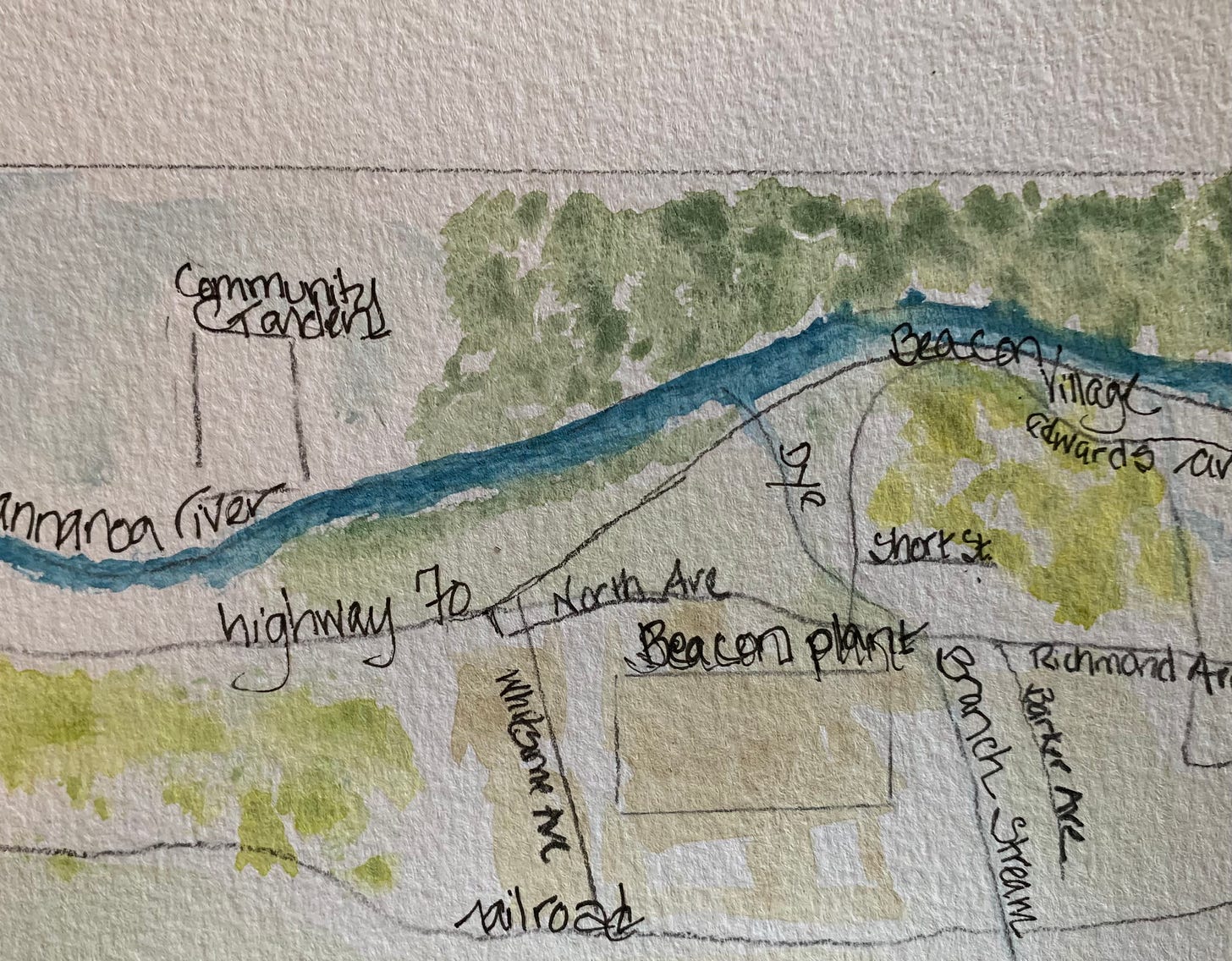

Textile mills are also a dirty industry. Beacon Manufacturing is a classic case of a northern company usurping a southern location for its resources. Charles D. Owen moved Beacon one thousand miles by rail from New Bedford, Massachusetts, to the Appalachian town of Swannanoa, North Carolina. The mill was reassembled into a one-million-square-foot facility on the Dye Branch Stream that feeds into the Swannanoa River. That changed the area from a rural mountain town to a mill village with company housing, recreation, shops, and entertainment.

According to the American Historical Association, in 1900, over 90 percent of textile workers lived in company housing. “Part of the intent was to discourage workers from unionizing. Everything was connected,” Swannanoa Valley Museum director Ann Chesky Smith said in a Valley Echo interview. “If you lose your job, you lose your housing.” But, the interview continues, “The dynamic of the relationship, however, often resulted in intense loyalty to Beacon for longtime employees, many of whom worked alongside family and neighbors for decades. The environment created strong bonds within the local community before the shifting landscape of the global economy led to its sudden closure in 2002.”

The filmmaker Rebecca Williams has been working on Blanket Town: The Rise and Fall of an American Mill Town. The documentary is an in-depth exploration of Beacon's legacy. With a focus on personal interviews with former employees, Williams brings out the community bond along with the reality of working in a textile mill. She said, “There was mobility and opportunity, but it was certainly a system with many flaws. It allowed the company to have a lot of control because people didn’t just depend on their employer for a paycheck, they relied on them for housing and so many other things.”

Beacon’s decline began long before 2002. In 1969, the Owen family ended ties with employees when they sold the last of their company stock. Absentee owners bought and sold the company over the next three decades. The sense of community was lost when the new owners prioritized stockholders over employees.

Recently, Rebecca Williams and I walked the banks of the Swannanoa River. We appreciated the deep beauty of the River, but we also noted the particles of the past, petroleum and acrylic from the Beacon factory could not be scrubbed out. Rebecca is a community activist and a storyteller. Her yet-to-be-released Blanket Town has been a labor of love for years. I have listened to her behind-the-scenes work with the eagerness of one who loves to be backstage. She has listened to me talk on and on about the Rights of Nature for the Swannanoa River. When we reached a resting place, I asked Rebecca for her thoughts.

“Act as if the River has rights.”

“Celebrate the river. Greet the Great Blue Heron. Thank the Brook trout. The river wants you to pay attention.”

Rebecca asked, “Can you hear the voice of the river?”

I was silent. I thought about the article my sister had sent that morning. It was Glacial Longings by Elizabeth Rush. The author traveled to Antarctica as a writer in residence, one of the 57-member crew aboard the Nathaniel Parker. Their mission was to study the Thwaites Glacier as its demise predicted consequences for coastal shorelines. Rush wanted to know if she could hear the glacier. But she realized that she had not been in Antarctica long enough. Her body wasn’t calibrated to hear or understand the glacier.

“I can listen,” I said to Rebecca. “It’s too soon to tell if I can understand what the River is saying. And too soon to know if I have the right to translate her message.”

I’ve had a business in the Swannanoa River Watershed for 17 years. I have lived “here” long enough to actively participate in the community. But not long enough to answer “here” when that steadfast southern question surfaces: Where are you from?

I know the Swannanoa River well. But Rush’s article raises questions: do I have the proper calibration to understand the River? More than anything, Rush renews my humility in approaching the River.

I know I have felt the River. Last Thanksgiving, a few friends gathered. I put my hand in the cold November water and felt a slight tug; the River acknowledged us, acknowledging her.

In my journal, a love note from that day:

Good people of the Swannanoa River Watershed,

I think you sense that the days ahead will be difficult. You work with well-intentioned people on your Town Council and town staff. I think you know larger forces are at work in your state capitol.

I ask three things of you:

Remember that I am an Appalachian River. I am gentle, and I am fierce; I am complicated. If you core my mud, you will find toxic evidence from Beacon Manufacturing that flowed from the Dye Branch stream. Protect me, at all costs, from people who view themselves as separate from nature., particularly when they have power.

Celebrate me. Visit me. Bring friends. Thank the vast Watershed for draining into me. Remember, we are upstream. Our job is to protect those downstream beings: the French Broad River, the Ohio River, the Tennessee, the Mississippi, and the Gulf of Mexico.

I am a being who remembers everything. I have the right to be here, evolve, and flourish. I nourish you. My love for you has no bounds…it is beyond measure.

Katharine🌱

Footnotes:

Brian M. du Toit, Ecusta and the Legacy of Harry H. Straus, Publish America 2007, 38

John. E. Ross, Through the Mountains: The French Broad River and Time, University of Tennessee Press, 2021, 184

Keep sharing these stories Katharine. Awareness is the first step in initiating others to take action.

Also, lovely writing!✍️

Thank you for this education: from my mind, my body and my heart.