June 4, 2024

Scientists who can explain how nature works inspire me. I am particularly in awe of scientists who weave dry science into stories that we, the everyday people, can understand. I think you know that Robin Wall Kimmerer is that scientist for me. I look for writers like Kimmerer to share with you.

For several years, the marine biologist Ayana Elizabeth Johnson has captured my mind and heart. Her work intersects marine science and environmental justice. She is the co-founder of Urban Ocean Lab, she teaches at Bowdoin College, and she is the co-editor of All We Can Save: Truth, Courage, and Solutions for the Climate Crisis. Johnson, forty-three, is wildly intelligent, funny, and beautifully human. Her forthcoming book is What If We Get It Right? Visions of Climate Futures.

The New York Times published an interview with her called “This Climate Scientist Has an Antidote to Our Climate Delusions” on May 18, 2024.

Johnson talked with David Marchese about possible climate futures: renewable energy, improved public transit, and reduced consumption. She echoes a message from All We Can Save — the climate solutions have already been invented; now they need to be implemented. She notes that Biden’s Infrastructure Act has already created training, jobs, and lower energy bills, especially in the very red states.

Johnson concedes that getting it right does not mean pristine or perfect. “I’m not an optimist. I see the data. I see what’s coming. But I also see the full range of possible futures.” Johnson's message echoes that of Robin Wall Kimmerer: we are one of many species, and our practice is to be kin.

What prevents us?

“We have a divided and underinformed populace, and that makes everything so much harder. The climate crisis is going to give us a lot of tests on how we can collaborate across various social divisions,” Johnson says.

David Marchese admits, “I don’t know how to think about the future.”

Johnson: “What are you afraid to give up?”

Marchese: “Comfort.”

Johnson: “That’s good of you to admit. I think we all want to hold on to our comforts.”

Marchese: “Is there an antidote to that kind of thinking?”

Johnson: “I think the answer is in community…You can maybe grip tightly onto your comfort in the short term, but the more we resist being part of the collective solution, the less likely the collective solution is going to happen. In a sense, you’re echoing a bit of this bunker mentality where we have these megaweathy people who are buying up land in New Zealand and wherever else trying to save themselves. That seems like such a sad way to see the world. Like, do you want to live in a bunker for a year eating canned rations? Is that the life we want to build? Or do we all try to make sure we have a world where there’s enough for everybody, where no one takes too much and we share what we have. I’d rather share.”

Johnson says she not calling out her interviewer. She says we live in a consumer culture. She shifts the burden of responsibility to the very small group of people who make the significant decisions that affect millions of species.

“There are actual fossil fuel, advertising, and big agriculture executives, and politicians who are enabling all of this. There are individual humans, actually quite a small group of them, who are making these decisions that impact life on the planet. That should make you mad because who are they to decide about life on earth and to be so callous and so short-term thinking and so quarterly earnings and shareholder dividend driven that they are jeopardizing biodiversity and the quality of life for everyone?”

That quote of Johnson’s is in The New York Times podcast version but not in the article. One thousand one hundred and thirty-nine people commented on the article before the Comment section closed. I read most of them. As a species, we sound somewhat cranky and, sometimes, confused. One astute commenter pointed to the exact spot where Johnson’s remarks — critical of big powers — begin and end on the podcast (14.10-14.55). The commenter lamented the omission in the written version.

Given the tremendous power that advertising revenue wields over the newspaper, it’s surprising that Johnson’s quote remained intact on the podcast. I acknowledge the paper’s prerogative to cut Johnson’s 45 seconds, which highlights the abuse of corporate power. Still, it’s a signal that quite a small group can sabotage the planet and influence how we live. In this example, they have muffled the communication between the scientist and the public.

I need a personal moment here. In this time of change in the publishing field, I appreciate what the big houses and publications can do for the greater good. Yet I really really appreciate Substack. As a writer, I am delighted that Substack provides a place where we can create and ship to our readers in an expeditious and caring way. That feels necessary right now. Thank you

and crew. Thank you, dear readers!According to Johnson, 62% of Americans feel a personal responsibility to help reduce global warming, and 51% say they don’t know where to start. How could we? It’s almost impossible not to be influenced by that small group of politicians, fossil fuel companies, big agriculture, and advertising executives. What happens when we subject our intellect to a constant barrage of advertising? What happens when a cultural institution cuts the truth out of the heart of an interview? How do we deal with the cultural desire to continue living the way we live?

We are at an inflection point. It feels, to me, like we are in an estuary. For some, estuaries can feel brackish or mucky. That’s understandable. Yet when we think about the many species that collaborate in estuaries, we might pause to study how they get along. Estuaries are those places where saltwater meets freshwater. They contain the rich biodiversity of the watery world. They breathe between the land and sea. What if we took a collective breath? What if we sat in council and passed the talking stick or the microphone? What if we listened? And what if listening to each other included listening to the estuary, the muskrat, and the Great Blue Heron — our 1.5 million-year-old cousin, with their genus Ardea, dating back 14 million years?

I’m going to channel

, the master of nature and environmental action lists. What are the little things we can do daily that will make a substantial difference over time?I’ll go first. For context, I tend to start small. It’s my way of taking that first step.

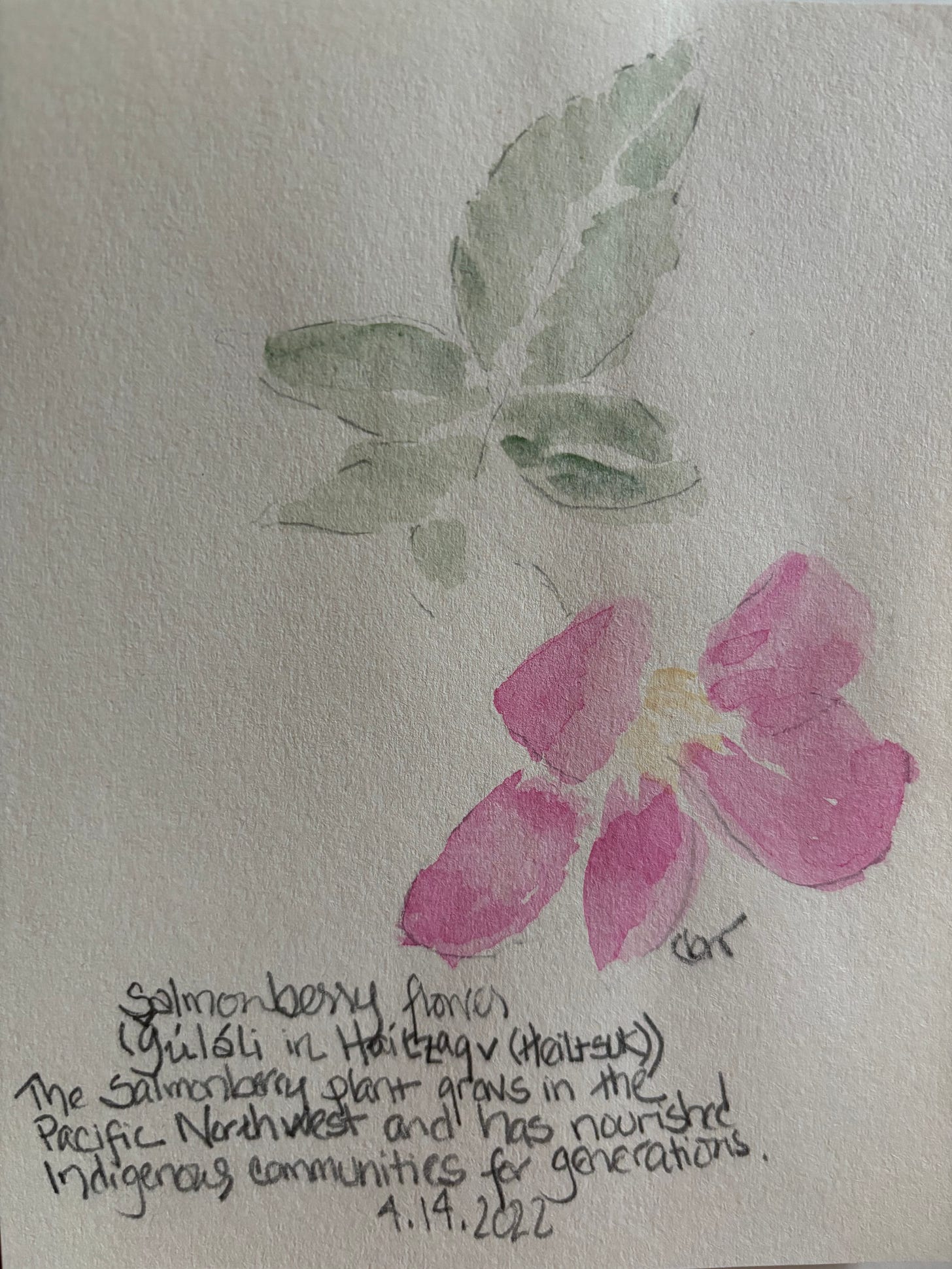

Keep a nature journal. Some days, I write a few lines. On other days, I’m more elaborate, writing extended pieces and dipping my paintbrush in water. My objective is to observe and record the more than human world. My attention extends to trees and water, chipmunks and acorns, and so many shades of green. I am an apprentice to nature.

Pick an environmental action community. I choose to work on Rights of Nature. The proposed amendment we wrote for our town charter is pinned to my bulletin board as we decide whether to expand our focus statewide.

Do the work that calls you. I love to write. My work here on

is my way to research what others might not, and translate that into story.Do what love calls you to do. Love calls me to summon my courage. I am inspired by writers who challenge society’s mores. In particular, I look up to Terry Tempest Williams. Just before I published this piece, the environmental artist Nancy Winship Milliken (my sister❤️) forwarded the Middlebury College commencement address featuring Williams. In recognition of the recent college encampments, Williams talked about her arrest for civil disobedience. Decades ago, the US government began bomb testing in the Utah desert. There was radiation fallout. Nine women in Williams’ family underwent mastectomies, and seven of them died from breast cancer. Williams attended a protest and was arrested. As one officer handcuffed her, another bodily searched her. The officer found her notebook and pen inside her boot.

Officer: “What’s this?”

Williams: “Weapons.”

Their eyes met. The officer tucked Williams’ pant leg back over her boot, notebook and pen in place. Williams says she became a writer in that moment.

I look forward to your comments.

in kinship,

Katharine

🌱Author’s Notes:

HONORING

I want to honor Ayana Elizabeth Johnson’s co-editor from All We Can Save.

Katharine K. Wilkinson continues ALL WE CAN SAVE as a project with far-reaching social and ecological benefits. Her mission is to nurture climate leadership, and she’s curated a world of resources at allwecansave.net.

My friend Mallory McDuff, a Warren Wilson College professor and frequent resource for this publication, just returned from the latest All We Can Save retreat in Georgia. Mallory said the retreat was well-facilitated with faculty and staff working on climate, from student mental health counselors to climate scientists.

“I’ve admired and written about Katharine Wilkinson for years, since I first heard her give a version of her TED talk to a packed audience in Asheville, NC. As a writer, speaker, and facilitator, Katharine brings her full self to any endeavor — her keen intellect, her poise and grace, her emotions, and her belief that "all we can save’ is worth fighting for — not in a line of battle, but rather in a circle of caring for each other and the places we love.” Dr. Mallory McDuff, author of LOVE YOUR MOTHER: 50 States, 50 Stories, and 50 Women United for Climate Justice.

WHAT I’M READING

The Backyard Bird Chronicles by Amy Tan

This book is traveling everywhere with me. I can’t put it down. Amy Tan pulled hundreds of pages from nine of her journals. The Backyard Bird Chronicles is a record of Tan’s obsession with nature and her growth as an artist. I can’t wait to share more with you.

Sources:

This Scientist Has An Antidote to Our Climate Delusions:

All We Can Save: Truth, Courage, and Solutions for the Climate Crisis co-editors Ayana Elizabeth Johnson and Katharine K. Wilkinson, One World, 2021

I’m looking forward to reading the articles referenced. It’s quite horrifying that the fate of the planet is in so few hands.

I read the NYT article and I also commented and read a good number of comments. Here is my response. We, each of us, can reduce our personal consumption by 10 percent in a year. See where that takes us. I think we will all be surprised by this attempt; we might give up a little convenience, but not comfort.