“If language shapes how we relate to others — human and non-human — then the words we choose may determine not just how we treat them, but whether they survive at all.” Robin Wall Kimmerer

“Words make worlds. In English, we ‘it’ rivers, trees, mountains, oceans, birds and animals: a mode of address that reduces them to the status of stuff, and distinguishes them from human persons.” Robert Macfarlane

🌱

In the years that I have studied Robin Wall Kimmerer and Robert Macfarlane’s work, I have come to more fully appreciate the power and beauty of language. For too long, the word ‘it’ pervaded my vocabulary. My mind is content when I say ‘kin” instead of ‘it’. The words we choose play an important role in the stories we tell. The words we choose, collectively, speak volumes about our culture. For a time, in the United States, the catchword was ‘whatever.’ An unenthused throwaway retort that could pierce the listener.

The latest cultural slang - ‘grab.’ is used to pressure a consumer or anyone to do something. Supplies might be scarce so get it now, or the sale might end, or the speaker is preoccupied with power.

The word ‘it’ has been associated with “objects’, including animals and even people. The globe became colonized and the dominant forces declared humans to be the superior species and all others as just ‘its'.’ We owe deep gratitude to Robin Wall Kimmerer for pulling back the veil to reveal that yes: rivers, ponds, streams, lakes and estuaries are alive, as is the ocean who gifts Nitrogen 15 to salmons who gift that nutrient to forests on their final journey to their natal stream.

We are kin. We are all essential to our ecosystems as well as the global ecosystem. In Potawatomi, Kimmerer’s First Nation language, animate beings are subjects, not objects. Kimmerer calls this the grammar of animacy. If grammar charts our relationship with others, perhaps a grammar of animacy will lead us to more peaceful ways. Kimmerer invites kinship into our language by asking us to consider using kin (plural) and ki (singular) as alternatives to “it.”

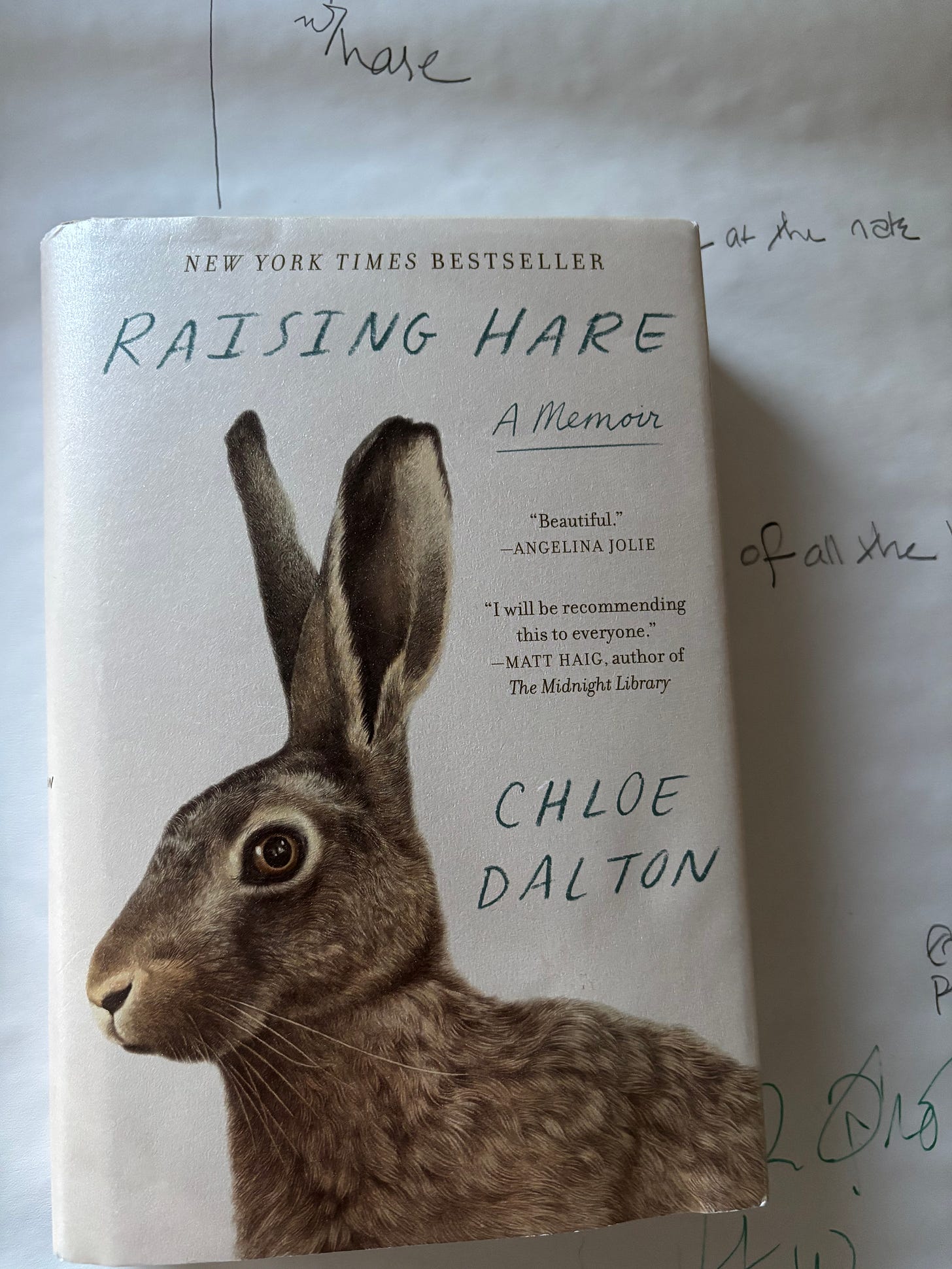

In Issue #34, I wrote about Raising Hare, the story of kinship between an abandoned baby hare (a leveret) and the author. In an experience Chloe Dalton describes as singular, she tends to the hare with the intention of an eventual return to the wild. Dalton calls the hare ‘it‘ until she knows that she’s a she (the hare produced leverets!). Initially, I was put off by Dalton’s choice of ‘it.’ Yet as I read on, I realized that Raising Hare demonstrates rare examples of kinship in action. Raising Hare is written in the grammar of animacy. Surely Dalton would call the leveret ‘kin’ were she familiar with Kimmerer’s work.

As such, the leveret changed Dalton and her relationship to the countryside of England. She adapted her life to the leveret’s. She left the garden door ajar so the hare could come and go. Thus, the self-described ‘London girl’ became acquainted with the sounds of the night: the owl’s call, the migrating geese.

Dalton did not turn on the electric lights because she wanted the hare to retain her night vision. Thus, she went to bed when she could no longer see to read. She found herself tiptoeing through the house so as not to wake the hare. She asked visitors to keep their voices down so as not to startle the hare.

As Padraig O'Tuama wrote in Poetry Unbound, Dalton “writes with an intimacy and privacy that I found deeply moving.” Beyond being Dalton’s memoir and the biography of the hare, nestled in the chapters is a thoughtful account of how the hare population in the U.K. and Scotland has declined by 80% over the past century. The most notable reasons are habitat loss and hunting.

There is slim research on this mythic and mysterious, quick-to-flee creature. Hares are sometimes mistaken for rabbits but they are faster, larger, and more playful, distinguished by powerful hind legs and dark markings on the tips of their long ears and tails. Their fur is a brilliant layering of caramel, sepia, and deep, deep brown. Their coat is so well designed that Dalton almost mistook the leveret for a rock on their first meeting.

Dalton’s home is a renovated barn that was once used to store tubers. Most of the year, the surrounding fields belong to hares, larks, deer, rabbits and grasses while potatoes grow underground. At harvest time, mammoth machines, optimized for efficiency, are delivered to the fields. After the hare came into her life, Dalton felt the need to take a closer look at the results of a recent harvest. Ten feet in, she came across the corpse of a leveret. “…pulverized, evicerated, churned into the dirt, along with the scattered potato roots around it.”

She writes, “I stood at the edge of the fourteen-acre field and wondered with a sinking heart how many other leverets, or indeed ground-nesting birds, had been crushed beneath those implacable wheels and now lay within the ridges or lost to sight against the rutted brown earth. It was just another day, just another harvest, a scene replicated up and down the land and across the world.”

Dalton turns back. She can not venture any farther into the battlefield of wounded hares, birds and fawns.

Reflecting on what she’s witnessed Dalton contends, “We have forgotten our dependence on the natural world, along with our appreciation for those who grow our food, who are in many ways the custodians of the land and who face relentless economic pressures. Our wider value system is distorted and the price is paid by the powerless, be they human or animal. As in so many areas of human endeavour, if we are not attentive, there is blood in the harvest.” Chloe Dalton

Dalton notes that fields were once ploughed at the rate of speed at which a man walked. This practice lasted through the 19th century. In Europe and in North America, even into the 1850-1870s, most ploughing was done with horse or oxen; the harvest was cut in slow, deliberate passes.

The advent of internal combustion engines initiated harmful changes to our nonhuman kin as the industrial age became a force. By the middle of the 20th century, tractors were commonly used on large farms. By the 1970s, harvesting machinery was capable of mowing hundreds of acres a day.

Hares are challenged with each technological advance that delivers efficiency to farmers. Brown hares evolved about 4-5 million years ago. Their rear legs are designed for speed. Their adaptation to stillness, camouflage, and acute hearing were tuned to grassland predators and seasonal rhythms. In their sensory support system, they have more than 100 million scent receptors, twenty times that of humans. What took millions of years to shape can be erased in a few decades of a mechanized harvest. Hares freeze when they sense danger. They read their surroundings as they make an escape plan. But by that time, the blades are already upon them.

Dalton wonders, “If it is possible to create robots and drones to reap our fields for us, could we not use technology to detect the presence of leverets, and fawns, and nesting birds, and could reasonable efforts not be made to relocate them rather than simply leaving them to be crushed beneath our machines?”

She also noted that we have unduly stressed the hares’ foraging lanes by eliminating hedgerows, using every inch of the field. Chloe rebuilt her hedgerows with the permission of her neighbors. They, in turn, converted the fields to organic farming, planting herb and legume tracks to improve soil structure and creating wide wildflower margins around each edge so that ground-nesting birds and hares might use them as shelter and breeding grounds.

🌱

Raising Hare has inspired other writers to examine their relationships with small creatures. Bill Davison, of the Substack - Easy By Nature, wrote “The Universe in a Rabbit’s Eye: Cottontails and the American Soul.” Bill’s essay is so evocative of Dalton’s style that I asked if he had read Raising Hare.

Bill responded: “I love that book! It is such a remarkable story. I read it a couple of weeks ago and that is what prompted me to write this essay. I intended on mentioning Chloe’s book and including quotes, but the essay took an unexpected turn.”

Bill writes, “What hunters know, and what science is now proving, is this: we are pursuing creatures whose intelligence operates in dimensions we can barely fathom. When a rabbit freezes at the first hint of danger, it's not paralyzed by fear but processing information—wind direction, distance of threat, proximity of cover—through senses so acute they make our perception seem like fumbling in the dark.”

🌱

Language used in common metaphors can distract us from the truth. “Going down the rabbit hole” has become shorthand for spiraling into obsession or illusion — a reference to Alice in Wonderland, where a burrow opens into a world of absurdity and revelation. But in reality, rabbit holes are rare. Only one species burrows into warrens -the European Rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus), native to a small region of northern Europe. Although the species has been introduced beyond their native range, most places use the rabbit hole metaphor as if all rabbits lived underground in warrens. This metaphor contributes to the body of common phrases that disconnect us from ecological reality.

Most rabbits, and all hares, live exposed, above ground. The Appalachian Cottontail sleeps in grasses. A leveret is born in a shallow form on the forest floor. When we stretch the metaphor too far from ecological truth, we risk our already fragile relationship with our kin in the natural world.

🌱

I now look beyond the beauty of my place for ways to live in kinship. I wondered if a local situation paralleled that of the hares’ dramatic decrease in the U.K.. What I found was surprising. Snowshoe hares once lived in North Carolina. It is worth noting that there is no known date as to when they went extinct. What we do know is that their demise happened during a broader period of range contraction related to climate change and habitat loss. We exert more pressure on the land than many species can tolerate. Silently, a species can slip away when we exclude the voice of nature in our votes, our town council meetings, our neighborhoods and our homes.

Appalachian cottontails were recognized as a distinct from Eastern cottontails in 1992. Already, they face the threat of extinction. They need cooler temperatures and shelter such as spruce-firs. They live at an elevation of 2000-2500 feet. Warmer temperatures, increased mountain top land development and hurricane damage challenge the Appalachian cottontails’ population.

Why does all this matter? Hares and rabbits are essential to their ecosystems, which in turn affects relationships in and between more ecosystems. Hares and rabbits contribute to soil health. They are food sources for larger predators.

If the Brown hare goes extinct, the grazing system will go out of balance. Hares are selective; they trim grass tips, stimulating regrowth and maintaining plant diversity. Many soil organisms and pollinators rely on the results of the Brown hare’s work. Hare droppings are rich in nitrogen and phosphorus. Without those nutrients, there could be changes in soil microbial communities.

Foxes, buzzards, owls and stoats rely on the hare as prey. These predators may stress other fragile species if they have to resort to hunting prey such as ground-nesting birds like larks.

When Appalachian cottontails go extinct (as they will without significant intervention), we need only to look at the fragmentation of their habitats, interrupted by roads (notably paved roads) and grand second homes in higher elevations. Their extinction would signal a broader collapse of the fragile mountain ecosystem. Each time they hop or make a nest or a bed, they aerate the soil. Every time they choose one of your lettuce leaves, that’s an indication that your soil is healthy. And they add to your soil’s health when they excrete pellets rich in phosphorus and nitrogen.

When Appalachian cottontails go extinct, predators such as the great horned owl, the red-tailed hawk, coyotes and bobcats will have less prey and may turn to other fragile species.

Despite Hurricane Helene, the Eastern cottontails are usually in view, given their preference for this meadowland. Yet our language that refers to ‘multiplying like rabbits’ is not indicative of a stable species. They are faced with the same threats that affect the Brown Hare and the Appalachian cottontail…habitat loss, pesticides and hunting.

An additional threat lurks that affects all rabbits: Rabbit Hemorrhagic Disease Virus Type 2 (RHDV2). The disease is in the western U.S. in native rabbit and hare species. Our North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission is actively monitoring the disease’s path with the assumption that RHDV2 will arrive here. The disease only affects rabbits and hares but the mortality rate is high at 80%. (The Appalachian cottontails are particularly at risk because their shelter, the spruce-fir forests, is declining due to disease and invasive species.)

Habitat conservation efforts are urgent for the long-term survival of our elegant kin who play a quiet but critical role in land management and the food chain. They are essential in the loop of reciprocity. A healthy, less-stressed cottontail population with food and habitat resources will be better prepared to survive RHDV2. If we lose the rabbits, we would lose the quiet stewards of the edge of the field and forest, yard and woodland. Their health and numbers reflect the quality of transition zones which are rich in biodiversity but vulnerable to development.

In my meadows, I'm planting Red fescue grass for its high protein content and Kentucky bluegrass for year-round growth—small acts of kinship that could make the difference between survival and extinction for the cottontails who visit my garden. Many of my neighbors are making greater acts of kinship for the land that they steward (or who stewards them). Lucy, down at a slightly lower elevation, teaches me the relationships between what she plants and who visits her large meadows. She and her partner moved here to make a small home and a large sanctuary for all the creatures. When I visit, inevitably, a bird or small creature will hop along at a safe distance as we walk the meadow paths. They trust Lucy. The crows follow her car while she parks, and yap at her until she delivers their treats. When I leave, I tell Lucy I’m taking some of her magic with me.

What if we could make peace with the natural world? What if we could make our language more tender, more reflective of our kinship, more solution-oriented? Chloe Dalton’s story is a lantern along our way to reverse the damage we have done to the earth. Chloe’s work elevates the tiny hare, steeped in myth and mystery, to the level of the large, exotic, endangered creatures who attract great attention. Presently, Dalton is leading the campaign, with the British government, to put limits on the hunting of hares. If Chloe Dalton, whose work is writing and advising foreign policy in high-conflict countries, can fall in love with a hare so much so that she brings her parliamentary speechwriting skills to us in the narrative of her life with the hare, imagine what any one of us can do.

I treasure your attention. Thank you for reading all the way through!

In kinship,

Katharine

🌱

Resources:

Raising Hare, Chloe Dalton, Pantheon Books, New York, 2025

New York Times Review: https://www.nytimes.com/2025/03/01/books/review/raising-hare-chloe-dalton.html

The Guardian Review: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2024/nov/01/raising-hare-by-chloe-dalton-review-woman-meets-leveret

The Democracy of Species, Robin Wall Kimmerer, Penguin Books, 2013

Is a River Alive, Robert Macfarlane, W.W. Norton, New York, 2025

Substack: Looking and Looking at You Looking by Padraig O’Tuama,

https://substack.com/home/post/p-168653085Substack: The Universe in a Rabbit’s Eye: Cottontails and the American Soul by Bill Davison,

https://substack.com/home/post/p-168388302Lauren Graeber, my outstanding editor

🌱🌎🩵and all the interviews I could find with Chloe on YouTube.

That means so much coming from you. Thank you for listening to me whine my way through the challenges of finding credible resources!!🌱🌿💚

Katharine, congratulations on a powerful and persuasive and beautifully written essay!